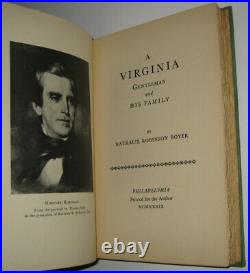

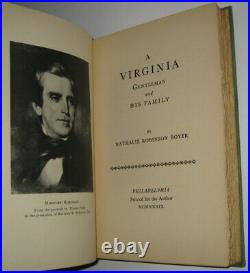

VIRGINIA SOCIETY! History Railroad Engineer America(SIGNED, FIRST EDITION!)RARE

Limited to only 300 copies, of which this is #5. Printed on Japan deckle-edged paper.

The type has been distributed and the book will not be reprinted. Illustrated with full page plates of portraits. Embossing of a deer on cover. Bound in the original binding. 9.5 inches tall, being a large and heavy book.CONDITION: Some external wear to the binding but in exceptional condition. Printed on quality paper that is extremely well preserved. Hinges are fully attached and sound.

Some general external rubbing/wear, as shown. Minor edge stain on blank end paper.

Clean, bright, fresh, and FINE internally. This is the First Edition. This limited Edition Consists of 300 Numbered Copies.

Printed on Japan deckle-edged paper, bound in boards with cloth back and leather label. Includes a frontis and a list of illustrations. A desirable piece of Americana and early society. Biography of Moncure Robinson and his children.The author was one of Moncure Robinson's children. Pages 123-200 are a biography of Nathalie Robinson Boyer (the author).

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Moncure Robinson (February 2, 1802 - November 10, 1891) was an American civil engineer.

Railroad planner and builder and a railroad and steamboat owner. Who is considered one of America's leading Antebellum period. He was educated at the College of William and Mary. Where he studied to be a civil engineer, and his most noted project was the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad.Unlike many of the engineers of the early nineteenth century, Robinson did not receive his engineering education at West Point. He acquired his engineering education. Through self-directed study and the observation of engineering projects throughout the United States and Europe.

Within nine years of the introduction of the first steam locomotive. In the United States, he surveyed, supervised the construction, or was the consulting engineer for 721 miles of track, or one-third the entire railroad track built to that time.

At the time of his death in 1891, over 163,000 miles of track spanned the country. Along with well-known engineers Benjamin Henry Latrobe, II. Moncure Robinson was in much demand during the late 1820s-40s and after, the transition period from America's Canal Era to the beginning of the Railway Age. By 1850, the basic technical aspects of the American railroad had been solved by this generation of engineers. Moncure Robinson was born in Richmond, Virginia as eldest son of John Robinson III (February 13, 1773 - April 26, 1850), judge and clerk of the court in Richmond, and Agnes Conway Moncure (1780 - November 15, 1862). Both parents were from the First Families of Virginia. The Robinson family presence in Virginia dates to 1688 at New Charles Parish. His mother's father, Peyton Conway, was the clerk of the court in Stafford, Virginia, and her family also descended from Scots immigrant Rev. And friend of founding fathers George Washington. His brothers were Cary, Edwin, Conway (September 15, 1805 - January 30, 1884), Eustace and Moore Robinson, sisters Octavia 1813?Map of Erie Canal, early 19th century. Moncure Robinson attended the College of William and Mary.

He was a student there until his expulsion in 1818. The College asked him and 21 other students to leave after a dispute involving the charges for a lecture class. In New York, and visited the Erie Canal. Aware that similar canal building was contemplated in Virginia, Robinson applied for a position with the Board of Public Works to survey a route from Richmond to the Ohio River. Danville and Pottsville Rail Road survey, 1831.Although denied a job because of his youth, the enthusiastic 16 year old Robinson was allowed to accompany the surveyors as a volunteer. Where he apprenticed on survey work for canals in his native state of Virginia before continuing his education in Europe, where he witnessed and learned from some of the world's first railroad operations.

Three years later, the Virginia Board of Public Works hired him to assist in locating an extension for the James River Canal. Robinson traveled to New York to view the construction of the Erie Canal, over a less hilly route than contemplated in Virginia. That visit convinced him of the advantages of railroads over canals as a means of transportation and an aid to commerce. His report to the Virginia Board of Public Works disputed the benefits of further canal development, and praised railroads in its place. The Board did not view the report enthusiastically.

He resigned his position and, at that moment, became devoted to the development of railroads. Robinson then traveled to Europe and further studied civil engineering. At the Ecole des Ponts et Chaussees, Sorbonne. In Paris from 1825 to 1827. Touring Europe, Robinson and studied canal, harbor, bridge and railroad engineering in England, the Netherlands.

First Passenger Train in N. (D & P) connecting the upper Susquehanna and Schuylkill rivers' canal systems with the coal fields in between.

Moncure Robinson remained an early advocate of railroads over canals, and came to direct construction of several of the earliest railroads in the country, including parts of the D & P railroad and inclines during the early 1830s. In 1829, Pennsylvania's "Main Line of Public Works" hired Robinson to survey part of the canal and railroad route from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh. His best known early work was the survey and design of the Allegheny Portage Railroad. The 36 mile combination of ten inclines and level railroad over the Allegheny Mountains, Hollidaysburg to Johnstown, which connected the state's canal on the east side with the state's canal in the Ohio River drainage on the west (the survey included the first railroad tunnel to be built in the United States). It became an engineering landmark.

Modeled after early British practices, some called it one of the greatest accomplishments of the Canal Era. Robinson also surveyed lines in the Mahanoy and Shamokin coal lands, eventually acquiring a part of the lands. All had inclines and connected to canals-still within the early British tradition of railroads being an adjunct to water/canal transport systems. While building one of the short coal railroads of the anthracite region Robinson also served as post master of Port Clinton, Pennsylvania. Where an early home of his still stands. Back in his native state, Robinson built the Chesterfield Railroad. A thirteen-mile coal road with incline, the first railroad in Virginia. He directed construction of other short lines around Richmond, Richmond & Petersburg. In 1833, at age 31, he was chosen as chief engineer for a grand railroad project from Richmond through Lynchburg, New River Gorge, and on to the Ohio River future route of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad.Although he completed a survey the company proved unable to raise funds for construction. And directed construction of the line including a spectacular stone bridge and a tunnel 1,932 feet long, considered his crowning achievements.

The 93-mile railroad built from the major anthracite coal fields of Pottsville to Reading and then to the port at Philadelphia was the first double track mainline in the United States (after the British model), included three of the nine first railroad tunnels in the United States, and was reportedly the first to use crushed stone ballast. (In 1828-9, Robinson had designed his first railroads-the Allegheny Portage and the Danville & Pottsville railroads-as double track lines, but these included inclines that worked better with two tracks; the Reading was the first main line designed at the outset with double tracks in mind, though with only a 22' wide grade that required widening later). Because of the extensive coal fields it tapped, the Reading would become one of the most profitable railroads in the U.

It was also considered Moncure Robinson's first mountain railroad without inclines-a statement about the transition from the Canal Era of franklin feeder coal roads to water transport/canals. The Reading paralleled the Schuylkill River navigation canal, and by the 1840s proved the superiority of the railroad over the turnpikes and canals as the inland transportation system of the nineteenth century. Table of Graduations of the Louisa Rail Road, commencing at Taylorville, 1836. Horses and mules, gravity and stationary steam engines on inclines, were the first motive power on Moncure Robinson's railroads. Though he held patents on incline systems, from the beginning, he recommended British built locomotives for railroads, especially the recently perfected 0-4-0s with Bury fire box.

By the mid-1830s, American mechanics had perfected the 4-2-0, with its lead swivel truck or pilot wheels - designed by John B Jervis for the Mohawk & Hudson - and Robinson recommended these for steeper grade railroads during the late 1830s, in Virginia and Pennsylvania. For the Reading, he ordered British and American made locomotives.For more power, however, he is credited with helping design in 1839 one of the earliest 4-4-0 locomotives, the "Gowan & Marx, " named after his London banker. This, the most powerful locomotive up to that time, was built by Eastwick & Harrison of Philadelphia, and proved ideal for the coal fields tapped by the Reading (John White, American Locomotives, correctly credits others for the 4-4-0 design patent; and this is true for the mechanics of the machine, but the concept of replacing the then dominant 4-2-0s with the better tractive 4-4-0s, which would become the major locomotive type for the next thirty years or more, has been shared with Robinson). In 1840, Robinson declined an offer from the Czar of Russia to direct an ambitious railroad building program, but did serve as consultant to the Czar, the US government, and elsewhere. About this time he broadened his consulting work, providing reports on the proposed New York & Erie Railroad. The New York Harbor improvements, and other projects.

In 1839, with Benjamin Latrobe, John Jervis, J Edgar Thomson, Claudius Crozet. Horatio Allen, Henry Campbell, and others he helped organize the American Society of Civil Engineers. In Philadelphia; although this organization languished he helped form a new AS of CE in New York in 1852. He was described as tall and handsome... With cold, gray eyes, an aquiline nose, and a scar on the left side of his face that ran from the corner of his mouth to his ear. Dilts, The Great Road, p. While working on the Reading, he undertook other railroad projects. He built the majestic bridge across the James River. For the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad.Which was completed in 1838. This 19-span bridge was the most impressive Town lattice truss bridge ever built in wood. Because of increased business in Virginia, he left his cousin Wirt Robinson as chief engineer of the Reading. Moncure Robinson became, between 1840 and 1847, one of the early presidents of the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad. He also continued to advocate for his unfulfilled dream of building a line from Richmond to the Ohio River to compete with the Baltimore and Ohio (Latrobe chief engineer), Pennsylvania (Thomson chief engineer, later president), and the series of lines paralleling the Erie Canal later organized as the New York Central (Jervis chief engineer), all of which built into the Ohio Valley/Midwest in the 1840s-50s.

Late 1840s Robinson was moving away from a career as civil engineer toward that of manager and financier. After successfully raising funds in England for the Reading railroad in the 1830s, he more and more turned to financing and directing projects, which occupied him for most of the rest of his life. He was an active stockholder and/or director of various rail and water transport companies-the Seaboard & Roanoke railroad, the Delaware & Chesapeake canal, Chester Valley Railroad, Pennsylvania Railroad, Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad, steamboats on the Chesapeake, and other properties-managing his holdings from his Philadelphia home. After the American Civil War.

Moncure Robinson, his son John Moncure Robinson, former Confederate general William Mahone. And North Carolina businessman Alexander Boyd Andrews. Successfully worked with investors to consolidate a series of short-line railroads into what became the Seaboard Air Line Railroad. They foiled an attempt by Thomas A.

Who had risen through the ranks of the Pennsylvania Railroad. And acquired the [Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad] after the war, from building a system along the eastern seabord. Instead, John Moncure Robinson became superintendent then president of this major, 800-mile (1,300 km) southern trunk line, from Norfolk and Richmond, Virginia to Atlanta, Georgia and Birmingham, Alabama. In 1887, at age 85, Moncure Robinson completed his last railroad construction project, the 18 mile Palmetto Railroad in the Carolinas, which helped link the Seaboard line from Richmond to Florida. Sons were John Moncure and Edmund Randolph Robinson. He was married to Charlotte Randolph Taylor (1815 - 1895) on February 2, 1835; she was granddaughter of the nation's first attorney general, part of the old Virginia family of Randolphs. He lived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Beginning in 1835 and intermittently until his death, as well as in Richmond, Virginia. Upon Moncure Robinson's death in 1891 in Philadelphia, eulogists remembered that as a young man he had been one of the new Republic's first railroad civil engineers. In his will of September 11, 1873, he left an endowment for preservation of the Aquia Episcopal Church.(his grandfather was reverend there, and his parents and many cousins of various degrees of descent are buried there-the Robinson trust still funds the cemetery's maintenance). And the papers of the Robinson family. Are held by the Special Collections Research Center. At the College of William and Mary.

Robinson left his profession as the leading railroad engineer in the United States, attained an international reputation for engineering excellence and marvelous executive talents, and was frequently consulted during his retirement on various railroad projects. He influenced Frederick List, called the "Father of German Railroads" and Michel Benjamin Chevalier, the Minister of Public Works under Louis Philippe and the most eminent engineer in France.

In 1853, the American Society of Civil Engineers bestowed one of its highest honors on Robinson by electing him an honorary member. Moncure Robinson is referred to as "one of the most distinguished civil engineers in the United States". And the genius of America's earliest railways.He was instrumental in the early development and growth of the country's great railroad system. Francis William Rawle, Moncure Robinson. Central Rail Road: Reports of the Engineers of the Danville and Pottsville Rail Road Company ; with the Report of the Committee of the Board Thereon, October 15, 1831.

Danville and Pottsville Rail Road Company. Report on the Continuation of the Little Schuylkill Rail Road: From Port Clinton to Reading.

Civil Engineers, upon the plan of the New-York and Erie Rail Road. Report of Moncure Robinson, Esq: Upon the Surveys for the Louisa Rail Road. Obituary Notice of Henry Seybert. The Virginia gentleman is a concept that attaches the qualities of chivalry and honor to the aristocratic class in Virginia history and literature. Which suggested a connection between Virginians and Royalists during the English Civil Wars.

So-called gentlemen were expected to lead and behave with courtesy toward all, regardless of social status. While not assumed to be personally flawless, they were expected to demonstrate fortitude, temperance, prudence, and justice. A gentleman's reputation and personal honor were to be cultivated and protected above all else.

Developed in the context of. And reaching its apogee among Virginians such as George Washington. The concept of the gentleman spread from Virginia across the South and became an important theme in early novels of the region. Just as the Virginia gentleman provided an aspirational ideal, so did these novels present the South and its enslavement of African Americans in terms that idealized the slaveholders.

This continued in the decades following the American Civil War. And the justification of slavery. While twentieth-century writers treated it with more irony, the Virginia gentleman still thrives in American popular culture.

The Revolution and Antebellum Periods. Take a cultural and historic tour through Virginia. The concept of the Virginia gentleman is inextricably entwined with the historical myth of the Virginia Cavalier. The most significant distinction between these two terms is that the cavalier ideal embodies more specific genealogical associations. Largely refuted by modern historians, this historical legend was widely accepted both within Virginia and beyond its borders during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.It asserted that the early settlement of the colony had been dominated overwhelmingly by thousands of aristocratic Cavalier followers of. During the English Civil Wars who fled the Puritan. Contrasting slightly with the Cavalier myth, the Virginia gentleman is a term more closely associated with the Tidewater plantation system that developed in Virginia in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It is defined by a code of gentility that expressed the ethos of these slaveholding colonial planters.

Because the plantation system was first established in seventeenth-century Virginia, the colony served as the incubator for both the Cavalier myth and the concept of the slave-owning gentleman planter. In the Chesapeake tidewater these notions were virtually interchangeable. In choosing to define himself as a nobly descended Cavalier Englishman, the colonial Virginia tobacco. Planter also defined himself as a gentleman, and he embraced a fully articulated code of conduct and manner of living.The seventeenth-century Virginia settler's ambition was to recreate in the new colony the country life of the English gentry. Thus the rules of conduct to which the colonial Virginia. Gentleman subscribed were copied from an Old World Elizabethan pattern. From the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries a loosely defined and flexible social code developed to mold the manners of the newly evolving class of English gentry, a code articulated in courtesy books like Thomas Elyot's. The Book Named the Governor.

(1622), and Richard Brathwaite's. This code of gentility strongly influenced the social attitudes of the plantation owners of colonial Virginia.

Regardless of whether they completely embraced the idea of Cavalier blood inheritance, by the eighteenth century Virginia's planters fully embraced the ideal of the gentleman, and they considered themselves to be the preeminent exemplars of the type in the new English colonies. This polished and cultivated self-image is clearly on display in colonial Virginia writing, from the poems and essays decorating the pages of Williamsburg's.To the supercilious descriptions of uncouth backwoods North Carolinians penned by William Byrd. The consummate eighteenth-century Virginia gentleman, in his.

History of the Dividing Line. Like his English counterpart, the colonial Virginia gentleman was expected to embrace the first commandment of the genteel code-the idea that men of high social rank were born to lead, while the vast majority of common men were born to follow and serve. Assured of his own social superiority the gentleman was nonetheless obliged to embody in his interactions with his inferiors the quality of noblesse oblige, to act with courtesy and thoughtfulness toward all, regardless of their social status. The Virginia gentleman sought to attain qualities of fortitude, temperance, prudence, justice, liberality, and courtesy. These Aristotelian virtues tended to supersede strict adherence to the Ten Commandments. Sins of the flesh, for example, might be forgiven if they were not blatant, excessive, or destructive of a gentleman's essential integrity. In colonial Virginia some degree of learning was thought to be essential for a gentleman.However, a refined social leader scorned crabbed pedantry that delved into esoteric subjects. A Virginia gentleman believed that the best and most useful knowledge was broad rather than deep. Learning was an adornment, worn lightly and gracefully, that-along with dancing. Fencing, hunting, riding, and occasionally the playing of a musical instrument-combined to produce a complete and smoothly functioning social creature. Writers of courtesy books were rather vague about the source of a gentleman's honor.

This quality was variously identified with virtue and with reputation. But though there was disagreement concerning its precise definition, there was substantial agreement with the notion that the primary purpose for a gentleman's following his code was to possess and maintain a reputation for personal honor that commanded the respect of all his peers as well as of all those of lower social order. The colonial Virginia gentleman placed great importance on the preservation of his individual honor.

Unlike his nineteenth-century heirs, however, he generally did not approve of dueling as an effective means of defending his reputation. Jefferson Impersonator at Poplar Forest. The code of gentility was thus translated across the Atlantic from the English rural gentry to the Tidewater Virginia planters who presided over moderate-to-large landholdings cultivated by enslaved labor, and it ultimately came to define the characters of planters throughout the South. From the eighteenth to early nineteenth centuries, wherever the plantations system spread into the middle and lower South, so too did Virginia's myth of Cavalier inheritance and the closely allied code of the gentleman. Yet even among the slaveholding gentry of the Deep South there was widespread acknowledgement that the Virginia gentleman had been the original and most exalted model of gentility and that he remained the most polished and refined example of the type.

Led by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, Virginia's landed aristocracy played crucial roles both in the achieving of independence and the formation of America's uniquely democratic national identity. Ironically, the independence to which the Virginia gentry.

Had so brilliantly contributed led to the swift collapse of the Old Dominion. S highly profitable tobacco trade with England. Despite the serious economic and cultural decline that befell the state's plantation economy after the Revolution, Virginia's gentry continued to maintain for decades an outsized influence in national politics.

Seven of the first fifteen U. Including four of the first five, were Virginia natives.

Virginians of the nineteenth century retained a proud consciousness of the vital contributions of their elite leaders to the establishing of the new nation. This pride was on prominent display in the works of Virginia's antebellum writers, which featured flattering and idealized portrayals of Virginia gentleman. The Knights of the Horse-Shoe; A Traditionary Tale of the Cocked Hat Gentry in the Old Dominion. Among the original fictional portraits of the Virginia gentry, George Tucker. (1824) and John Pendleton Kennedy's.

(1832) were set evocatively on plantations presided over by high-minded and proud country squires. Minor defects in the genteel characters occasionally could be detected within the overall admiring and sympathetic treatment, but the relatively tempered tone of early Virginia fiction vanished entirely in the decades preceding the Civil War. The Knights of the Golden Horseshoe.

(1845), fashioned completely idealized portrayals of colonial Virginia gentlemen. (1859) likewise retreated on the eve of secession into the golden age of the state's colonial and Revolutionary past, ignoring the obsolescence of its idealized heroes in an age of highly polarized political conflict. Indeed by 1860 the fictional Virginia gentleman had been fully enlisted in the defense and justification of chattel slavery. The Civil War destroyed both slavery.

And the plantation system, institutions that had served the state as the foundations of its genteel tradition. But the war did not diminish the Virginia gentleman's appeal either within the Old Dominion or in the nation beyond. In the ashes of the Confederacy's collapse. The white South conveniently convinced itself that the cause for which the region had fomented rebellion and disunion had not been cast into disrepute by defeat. To the contrary, it had been sanctified by that defeat and transformed into a holy Lost Cause.

Inevitably, the central figures of the Lost Cause myth were the South's gallant and chivalrous gray-clad warriors. Above all these war heroes Virginia and the South were united by their worshipful reverence. For the great military leader who epitomized their culture's martial aristocracy- Robert E. Indeed, the nobility of this great Virginia gentleman, even in defeat, appealed intensely to the imaginations of both white southerners and northerners. Drew upon Lee's inspiring example in his highly popular collection of stories.

This highly idealized celebration of Virginia's antebellum Tidewater culture served as a powerful fictional vindication of both the plantation system and of the state's honorable, high-principled, and racially benevolent gentlemen who had nobly sacrificed themselves on the altars of war. By 1900 the Virginia gentleman, though not enjoying quite as high a place in the nation's consciousness as he had during the age of Washington and Jefferson, still retained much of his favorable cultural appeal. But it was an appeal sustained by viewing history through a lens of sentimentality that tended to erase the violence of slavery.

It was also a concept that at its core was bound to white racial superiority. During the opening decades of the twentieth-century Virginia writers, informed by a new tradition of literary realism, began the challenging task of disentangling themselves both from romantic memories of the Civil War and from the state's idealized Cavalier warriors.

They resolved to treat their genteel characters with more irony and complexity. (1932)-strove determinedly to bring realism, "blood and irony" she termed it, to her treatment of upper-middle-class gentlemen. Though most of James Branch Cabell.

(1926) addressed with seriousness and wit the powerful allure of myth and cast an oblique light on the way Virginians who had survived the fall of the Confederacy had created their own pantheon of larger-than-life Cavalier demigods. The Confessions of Nat Turner. Later in the twentieth century writers such as. Began to engage even more provocatively with the idea of the Virginia gentleman. (1951) the writer described with a knowing eye genteel characters molded and also warped by contemporary Tidewater Virginia culture.

His Milton Loftis-a genteelly bred but undisciplined and morally soiled alcoholic-ventured daringly beyond the more tasteful spiritual lassitude of Glasgow's and Cabell's gentlemen. Despite the critical controversy that surrounded Styron's.(1967), the author unquestionably challenged the conventions of romantic Virginia fiction by describing the plantation system and its gentry though the eyes of an enraged enslaved black man. Refusing to capitulate to the romantic appeal of his novel's Virginia gentlemen, the narrative highlighted the fundamental irony that though these antebellum planters were not individually depraved, the system of chattel slavery that they controlled and forcibly sustained was.

Advertisement for Virginia Gentleman Bourbon. As America moves into the twenty-first century it is germane to question whether the currency that has for centuries been attached to the figure of the Virginia gentleman has not been completely spent. Surely the concept retains some vestigial resonance within the Old Dominion. The mounted Cavalier, the mascot for the.

Still gallops across the football field. The bottle label for Kentucky-distilled Virginia Gentleman bourbon still features squires gathered in front of a plantation mansion. But in a nation composed of ever larger numbers of black- and brown-skinned citizens who live amidst increasing social and political polarization and the subversion of traditional cultural and political norms, can the Virginia gentleman positively instruct our country today in any meaningful way? One can certainly make a case for the continued relevance to our society of the Aristotelian virtues of liberality, fortitude, temperance, and courtesy that furnished the foundation of the original colonial character ideal.

And considering the survival of this hardy concept in American for nearly four centuries, it would be perhaps premature to write the Virginia Gentleman's obituary. This item is in the category "Books & Magazines\Antiquarian & Collectible".

The seller is "merchants-rare-books" and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Year Printed: 1939

- Modified Item: No

- Topic: Fairy Tales & Fantasy

- Binding: Fine Binding

- Author: Boyer, Nathalie Robinson.

- Subject: Children's

- Original/Facsimile: Original

- Language: English

- Place of Publication: Philadelphia

- Special Attributes: Signed, First Edition, 1st Edition, Collector's Edition, Illustrated, Limited Edition, Luxury Edition